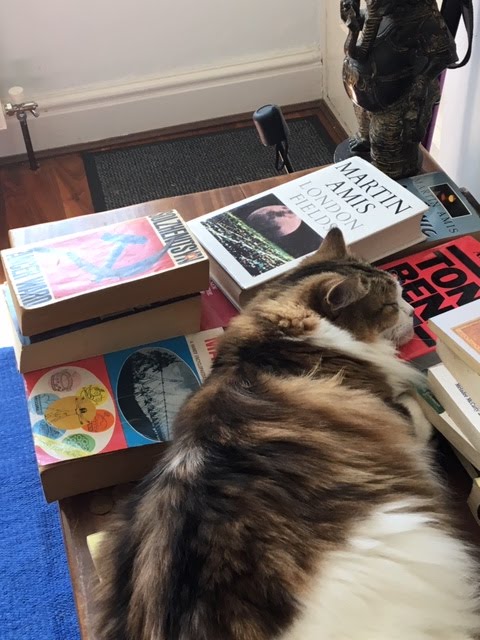

Boo boo in select company

Something to say?

Thursday, 20 April 2023

Our Monarchy

I am a Republican. There. I have said it. So, no one should be surprised that I have no patience for the pantomime showcasing the monarchy. Especially, Charles, the Third and Queen Camilla. Where is the halo?

I had a sneaky respect for Queen Elizabeth, the second. She was only a few years older than me, and I had watched her as she grew from a young teen-princess into a dignified monarch. When I was fifteen years old, I came by a glossy photobook about the two royal princesses. I spent hours looking at the pretty girls, Elizabeth and Margaret. I remember horses and dogs figured hugely on the pages. And George the VIth had been the King to whom we paid homage every morning in school assembly.

Until the police bundled my father off to jail in 1943 because he was a freedom-fighter and wanted the British to just get up and leave India. He was quite vocal about that. After that I refused to stand up when ‘God Save the King’ was sung in school. The nuns punished me in various inventive ways, and I insisted that George, the sixth, was no King of mine. And now – Charles. I rest my case.

In India, we have a democratic constitution, with a pseudo royal family, the Nehrus. Jesus wept! In a country with an enormous population, surely, there must be many who would better fit the role of leader of the Congress Party. In what respect is Rahul Gandhi a suitable Prime Minister? How has he earned the accolade?

Our country, the U K, is in a bad place at the moment, with many families finding it difficult to make ends meet. How is celebrating the advent of an inherited monarchy a priority?

Question – Do we need a ridiculous coronation right now? Or more social housing, more teachers, more doctors--- Money channelled into the NHS because it is crumbling now? Or even a quiet, unobtrusive way of ditching the Tory Government? I live in hope.

Friday, 24 February 2023

The Galle Face Beach

There was a routine in my husband’s home. Every evening, after coming home from work, Balan (my just-unwrapped husband) would take his parents to the Galle Face beach and park the car alongside all the other cars lined up, descanting families greedy for the evening air. He would then guide his father to the edge of the beach and the old man would walk the length of the beach and return to the car. Balan would accompany him on his slow walk while my mother-in-law stayed in the car. He is a good man, I would say to myself, about this stranger whom I had married.

Balan insisted that I accompanied the threesome in the evenings; I would sit in the back of the car with the mother and look at the crowds on the beach. Far away and across from us, the limousines drew up in the grand portico of the Galle Face hotel. Behind us the traffic speeded towards the Fort, the shopping enclave of the rich in the city.

I begged out of the daily Galle Face parade after a few days, much to the consternation of my husband; I started searching for reading matter. An addiction was waiting to be fed. In desperation at finding nothing, I went up to the disused storeroom at the top of our home. There was a Dutch almirah there with a glass front; I opened it, and the silverfish ran about frantically, as old books with yellowed pages tumbled out. All on religion, but I had reached a point of no return. I had to find reading material.

I grabbed a copy of the translation of Bhagawath Geetha in English, blew away the dust on it and took it down. Next day, my sister-in-law came by to tempt me to a dance. She saw the book I was reading and had a good laugh. ‘On your honeymoon and you are reading Geetha,’ she chortled.

I didn’t have the heart to tell her that honey and moon would not be enough for me. I was addicted to the printed word. And I did go for that dance where I fell in love with the joyous rhythms of the Singhalese Byela.

Tuesday, 24 January 2023

A Difficult Transplanting

Recently, my mind strays back to Sri Lanka. I haven’t been there since 1972; it was called Ceylon then.

I remember the enormous house, which my in-laws rented in Adams Avenue, Colombo. My ageing mother-in-law and rapidly disintegrating father-in-law rattled around downstairs, while my new husband and I occupied three humungous bedrooms and all mod cons upstairs. Once Balan, my husband, had rushed off to work, around 8 a m, I had nothing to do other than contemplate the view from the many windows.

From my bedroom I could see into a beautiful garden next door, so I did that daily. I would go downstairs for breakfast when all others had finished. At home, in Thalassery, it had always been Dosa or Idli with coconut sammandhi (relish). Bread, butter and strawberry jam didn’t cut it. I often made up with many cups of tea. Did wonders for my waistline – until the waistline came into its own with my first pregnancy.

I learned elementary kitchen Singhalese to communicate with the young Tamil maid, Pakyam, who reigned over a vast kitchen, where nothing much was cooked except my father-in-law’s insipid mushes. Pakyam had supreme contempt for me and didn’t like me around in the kitchen.

My kind sister-in-law, Kamala, would come round in her chauffeur driven Cadillac, once or twice a week, to take me ‘shopping.’ Shopping as a leisure activity was new to me. My father nurtured an extended family on an uncertain lawyer’s income; if there was any spare cash, it went to sustaining waifs and strays in his village. Kamala’s chauffeur with his peaked cap reduced me to silence.

Kamala would go to many shops in a day, getting material for sari blouses, garments for her niece, and odds and ends for the ‘sewing woman’ who came once a week to sew for Kamala. Clearly, this was an industry sustained by the posh Colombo -7 crowd, who kept the wheels of Kotlewala’s government turning, and subsequently, that of Bandaranaike. The Times of Ceylon would occasionally describe the fineries of the rich ones at some soiree’.

After a few weeks. I signed out of the shopping events and devoted myself to sitting on a chair on the veranda and day-dreaming. As usual with the pregnancy related practices at home in India, I would go home in the seventh month.

I counted the months out. Was I cut out for marriage? I wondered. I still wonder.

Friday, 20 January 2023

Where The Rain Was Born --- an exercise in nostalgia

Thalassery -- A verdant, little, coastal town, tucked away in the South-Western corner of India along the shores of the Arabian Sea. If you walk a long, long way north, hugging the coast you will finally reach Mumbai (formerly Bombay.) If, instead, you walk in the opposite direction, you will end up in the Arabian Sea, quite quickly, somewhere near Sri Lanka.

I always thought that Kerala, our state, was where the rain was born. When I travelled from Chennai to Thalassery, by the old Madras Mail, (so called because it delivered our mail -- why else! -- all the way from the east coast, at just after mid-day, every day) I would see how the terrain changed from barren brown to rich green as we came out of the tunnel, through the Western Ghats. I’d press my eager head into the horizontal bars of the train window, and breathe deep of that familiar smell of wet vegetation and home; with it I would also take in the particles of soot and ash that came out of the front of the steam engine, making my eyes itch and my hair gritty.

Well before the fears of global warming and consequent flooding, the monsoons arrived with predictable regularity each year, at the end of June, and swept away a few houses nestling precariously on the top of river-bunds. There was no welfare state as such, so the community, neighbours, had to step in. After several days of unrelenting downpour, the waters would rise and spread.

My father’s sister would have spent the whole month of Karkadagam, ( the Malayalam month that falls between the middle of July and the middle of August) known for disease, death and devastation,) chanting prayers to ward off the disasters. Generally Small-pox, Chicken-pox, Typhoid and Plague, arrived in the rainy season. The old women in the house, whose duty it was to guard against all evils that could be fended off with prayer and incantation read out of the holy book, Bhagava, at dusk and dawn, in front of the nilavilakku, the scared lamp.

But, of course, Chicken pox spread through the house and went. It lingered with one person or another and all of us waited for it to strike. That extended household had three children: myself and my father’s brother’s children, Mani and Appu, Mani eighteen months older and Appu four years older. My father’s niece, Nani, father’s sister whom I called Ammamma and father’s mother, Achamma, also lived there. So Chicken pox had quite a haul.

Achamma (father’s mother} always organised her second line of defence when disease got close – as in next door. She kept coconut shells filled with a cow-dung solution along both sides of our walkway to the front gate. This was supposed to ward off Mariamma, the evil goddess of Small pox. Maybe the same Goddess did duty for Chicken pox too. I had a mental image of this vile witch, grotesque and pock-marked. She haunted my dreams. She was always hanging about our front gate, working her way up to the house.

Wednesday, 11 January 2023

Animals

Animals

I cannot imagine a home without animals. In our house, who owns who is always debatable. When our fluff, Booboo, perches on Kitta’s knee when he is marking a hundred university scripts; when Pepper, my cat, complains as I move my legs in bed (My legs are solely for her to sleep on at night.); when the mutt, Lily, nudges my daughter’s legs aside on the sofa so that she can curl up in her lap, the answer is crystal clear.

I often wonder how it is that some families love animals and some don’t. Genetic, or exposure to pets early in life?

Next to our house in Thalassery there was a Chayakkada. Men going to work at building sites or factories stopped there, on their way, to get a hot cup of chai; my aunt said they probably never bought tea leaves or milk for their households, the morning drink generally being yesterday’s conjee. The chayakkada was a tiny roadside veranda and a small room with two rickety benches in it. It was run by a man called Kumaran, and when he washed his tea-pan out, he swung the dregs on to the road.

He had some saving graces. Every six months he would have another litter of kittens to give away, all fluffy-tailed and long-furred. They went quickly; in passing, our household got one or two. Achan disapproved of cats saying they caused asthma, but he was on a losing wicket. When he was near, we hid the kittens under the gatherings of our pavadas (long skirts) or later, my sari. Sometimes the kitten gave the game away by purring on my stomach.

My first cat was named Sundari. She was all white and had a beautiful face. The next one was Beauty, which meant the same thing. They had pretty faces and plentiful fur. They disappeared often down the road, scavenging at houses where fish was being scaled and finned, but returned to puke on our doorstep. Eventually, they would disappear into cat paradise – I would call their names without a miaow in reply.

The last one was Mimi; when I got married and left, my father, who maintained he disliked cats, arranged for the fisherman to feed her daily.

In my husband’s home, no animals were allowed. My husband’s parents did not like them either. So, it was not until I became single again that I got another animal. Leone and Makeni, the two dogs were named, after my favourite places – Makeni is in the north of Sierra Leone. I had to give them to friends to keep when I left Uganda for good. It broke my heart and I vowed never to get another animal.

Next year, in Zambia, (1993) I got Inji (Malayalam for ginger)– a majestic ginger tabby. By now, I could afford to take my cat with me, so Inji went with me to Malawi. Meanwhile my daughter, who was also in Malawi, had acquired another kitten – Ammu. A boy was holding some kittens up at a roundabout; predictably, she fell for it. Ammu drove Inji mad cavorting all around her and got frequently swatted. She came with us to England. Inji died of a kidney disease in Malawi, and Ammu became road-kill in Croydon.

In Croydon we got Tyson and Louis, (we never learn) forever fist-fighting as kittens. My little granddaughter called them Tyson and Nui-nui. Two road-kills again. I vowed I would never get a kitten after that, but my daughter came back one day with Booboo and Pepper, two tiny kittens that hid under a cupboard in the kitchen, until they were really hungry, and came out to eat. They are still with us, now five years old. Pepper sleeps on my bed and Booboo pesters my son.

There was also Keeri, whom I got in Kochi, and I brought home to England with me. She was adorable, intelligent and followed me around. She slept on my right shoulder generally, and would scurry up to bed with me. She also got run over in 2015. Now, my daughter won’t let me get another kitten. ‘They all die,’ she says.

We have Lily instead, a long-suffering, loving dog that does not recognise that she is not human. She is also thoroughly spoilt. We are right suckers for animals.

I’d love another Bengal-kitten like Keeri.

[ Pepper died of old age last month, at thirteen years.]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)