My uncle, Achan's elder brother, Sankaran Velyachan,, ran away to Malaya, in his late teens. He had good reason to run, rumour hath it. A maid in his house got pregnant and he might be forced to marry her, being the only bachelor in the house. So, he persuaded his sister to part with her gold necklace, sold it, and bought tickets to Malaya, before the elders in his household had added 2 and 2 to make 5.

A few years later, in Singapore, he became a doctor, licensed to practice medicine. This was not an uncommon story in the nineteen-twenties. From my father's family, two more young men ran away in search of fame and fortune. One worked in the post office in India when he returned home in the late forties after the war in the East had ended. The other didn't wait for the war to end; he returned to Madras (now called Chennai) in 1944, in a Japanese submarine, armed with many toys-for-spies. Actually, he just wanted to go home; he abandoned his spying goodies on reaching Madras, and forever after, was known in his village to which he vanished, as Japan-Balan. He was my father's nephew and I I knew him well. He was handsome, lazy, good-natured, and often drunk. But, there was no guile in him.

During the second world war many families were split up, with the men stranded in Burma, Persia or Malaya. My uncles's wife, however, was with him when the war started. He was in Penang and Singapore and Sungei Patani, working in rubber estates, until he returned to India after six years, with many hair-raising tales about the Japanese army in Malaya.

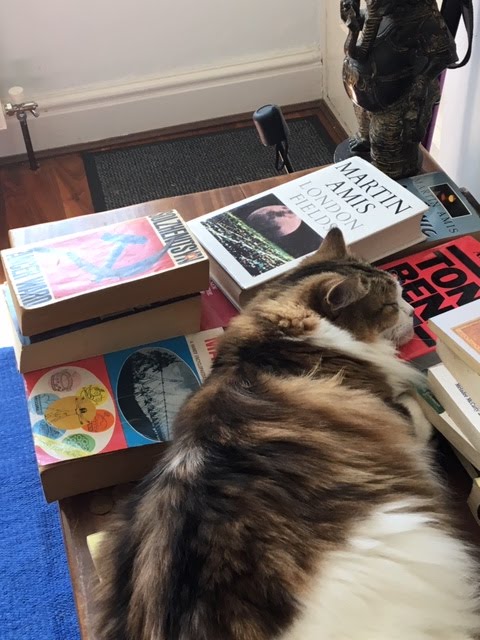

Photo specially taken for the edification of Velyachaan and Velyamma. We were dressed up for the event. Appu, being male, got pride of place on the chair. Of course.

In 1940, Velyachan sent his two children, aged six and nine, to Thalassery for their education. There were no schools on the rubber estates where he worked. So Achan became their beloved Elayachan (younger father.) Achan loved those two, Appu and Mani. (Sometimes I was jealous of Mani.) They melded into our extended family and I now had siblings. A money-order and the odd letter arrived every month for my father. When Japan invaded Malaya the letters and the money stopped. Subsequently, my father went to jail and money became a rare thing.

Velyachan and his wife, Velyamma, Ammu, were stuck in Malaya for six years -- when they returned in 1946, Velyachan's mother had died, and us children were now savvy teenagers. My father and I were sad when Appu and Mani went away with their parents in the direction of Velyamma's home in Ottappalam soon after. After that, I saw my cousins only during brief visits every year. I missed them; my father missed them.

UNTIL, both Appu and Mani became old enough to travel on their own. They ignored their parents and made a bee-line for my Achan's house and the town where all their friends and family lived. Velyachan gave them an education and lost their loyalties.

As I grew older, I travelled to India from wherever I was posted, once a year. I went straight to Mani's house. Wherever she was, was home.

She died two years ago and I now have no great desire to go to India.